The topic of this paper is heroism. The purpose is to show how heroism emerges in everyday life, and how it is significant in the life of an ordinary person. It covers a variety of aspects of heroism, in particular the heroes who have crossed my path, how their heroism has manifested, how heroism manifests in ordinary people, and some components that are present in a heroic life. I have used personal observation, a personal interview with a psychiatrist, and various published literature, including the Life-Span Development textbook. The conclusion of this paper is that by observing the lives of people we consider heroes, monitoring our own behavior, and modeling our behavior after heroic people, anyone can become a hero.

Heroism, Dignity, and Reality

I wonder what it really means to be a hero. It is surely tied in with living a dignified life and facing reality. Current and past critical family issues are helping to clarify the dignity issue now, so from that perspective, I am writing not only from need but also from pain. Especially, I am needing to face that pain in a constructive and life-affirming way.

Viktor Frankl (1984) points out the importance of finding meaning in life. In his book, Man’s Search for Meaning, he explores the stages prisoners go through and determines that it is only when they find meaning in their lives that they find the will to live, to survive. When I wake up in the morning, I do have a reason to live. Although I do not have the words just yet to articulate it precisely, the reason has to do with a task and mission that must have been charted out long ago, perhaps even before my birth. And although I don’t remember it, I met my first hero the day I was born.

The doctor who delivered me saved my life, literally. I was born with a defect known as omphalocele. The doctor happened to be a surgeon as well and he made a decision to operate on me without my parents’ consent. He risked being sued, but his risk was my family’s gain. I lived, and have the scar to prove it.

I thought about that scar in class one day during a discussion of the adolescent stage, specifically about the desire of teenagers to have plastic surgery. I clearly recall my childhood dismay over the surgical scar on my stomach since birth; it inspired feelings of inadequacy and difference from my peers, who (as far as I knew) all had normal belly buttons and not grossly deformed ones like the one I got stuck with. My mother assured me that when I got old enough, I could have it repaired by a plastic surgeon.

I assumed surgery would make things right, so I eagerly awaited that day. When I turned sixteen, my wish was granted and I had plastic surgery on my scar. The result was that I now had a different scar! It wasn’t what I had hoped, but merely a less severe disfigurement. Although disappointed, I accepted the results and continued my angst-filled adolescent journey.

Now, the older I get the more I realize the surgery I had was unnecessary. My birth scar has become symbolic. I stop short of saying I am grateful for it, but I am grateful in spite of it because of the heroic act it represents, the saving of an infant’s life by a man who trusted his intuition and took a risk that could have cost him his professional reputation and more.

I think about what might have caused the doctor who delivered me to make such a decision. I imagine a certain tension and conflict were present, the result of a battle being waged in his mind. This brings me to one of the points I wish to make, the way we use military terminology to describe ordinary, everyday events and circumstances.

I interviewed Dr. Joel Feiner, Medical Director of the Comprehensive Homeless Program at the Dallas VA Medical Center. He has gotten to know many veterans of military combat — people who have seen unspeakable violence, many of whom have perhaps even committed acts of the same.

When we came to the topic of heroism, the first thing Dr. Feiner said was, “I don’t believe that anybody is unflawed, right off the bat.” (It didn’t occur to me then, but it does now, that the birth scar I saw as so flawed in my childhood has come to represent something completely different now.) The next thing he did was to recite something he attributed to Philo, an ancient Greek philosopher. “Be kind, because the person you meet is fighting a major battle (personal communication, October 12, 2006).”

He went on to say that he begins every lecture he gives with the following statement: “Three things are important in life. The first is to be kind. The second is to be kind. The third is to be kind.” Dr. Feiner says if a person is not kind, he loses stature.

I think of kindness also in relation to the way we view ourselves. I have discovered that one of the most rewarding ways to be kind to yourself is to create art. It is a way to express yourself freely and without fear. In addition, it is calming and peaceful and the result is a kind of satisfaction that is difficult to describe.

W.B. Yeats believed art is made out of the conflict with the daimon (Hirsch, 2002, Yeats’s Daimon chap.). This word refers to a deity from Greek mythology; the dictionary suggests it might be a heroic deity (Pickett et al., 2002). It is also defined as an attendant spirit or genius. I cannot help but wonder how the word, also the related words daemon and demon, have taken on more ominous meanings over time.

The history of the word and its derivatives notwithstanding, one thing that comes to mind here is the tension between what is observed and what is determined as a result of that observation. The tension seems to be a force that leads an observer to do what he will do, make a decision or come to a determination or judgment. Here is an illustrative story. A family friend who lives in Richardson, where residents are currently voting on whether beer and wine can be sold in stores there, opposes the idea and put signs saying so in his yard and in other places around his neighborhood. The signs were later vandalized with graffiti. I thought of the difference between the person who would drive by his house and think the signs were good, nodding in approval, and the person who would be so offended by them as to want to destroy them. The same message can elicit different responses. One person might view the signs as being placed there by a courageous hero, willing to risk ridicule or worse for a cause he believed in. In contrast, another person could just as easily view the signs as a threat and become angry, so much so that he “speaks” to the signs (and to the people reading them) in a very visible way.

The word duende comes to mind as a possible name for this force or tension between observation and the kind of evaluation that leads to judgment then action. Duende is an Andalusian (Spanish) term that is not easily defined. Federico García Lorca’s work has inspired much thought about duende, which is — in simple terms — a kind of “frenzied earthly power” and a source of inspiration for art (Hirsch, 2002). Furthermore, Hirsh asserts there is “an inevitable conflict between power (the body, the conscious mind) and knowledge (the spirit, the unconscious mind).” I emphasized the word inevitable to draw attention to the fact that we cannot escape conflict and tension.

Duende can be seen in a poem by Yeats, “Ego Dominus Tuus,” which translates to “I Am Thy Master.” It consists of a dialogue between two figures given the Latin names Hic and Ille, which translate to This and That. According to Yeats, these voices are two opposing types: primary and antithetical. I view the force or tension (duende) as symbolic of a similar dialogue going on inside a person who is suspended in that space between observation and evaluation. Things are not always as they seem, at first glance.

Pat Schneider (2005) suggests we have a “primary” voice and that this is the one we use “all day every day in our adult home and place of work.” Furthermore, she writes:

It is the natural, unself-conscious way we talk to the people we most love and with whom we are most comfortable. It has taken on color and texture from every place we have lived, everyone with whom we have lived, and all that we have experienced. It has traces of our original voice — more or less depending on how much dialect or regional color was in the speech of our childhood family and how far life has taken us from that place (Schneider, 2003, 6th chap.).

Could it be that we also have a primary purpose — one thing that is prominent, the highest priority — and might it have traces of our original purpose? What all of this points to is that our primary purpose is linked to our primary voice; and if we don’t discover that, we might fail to realize our purpose, too. When a person uses his primary voice, he is speaking in a way only he knows how to speak. Likewise, when it comes to life’s subjective purpose for an individual, only he knows what it is.

Returning to Hirsch (2002, The Intermediary chap.), he makes a distinction between duende and what has come to be known as demonic. At the same time, though, he notes they might be unconsciously related. As an example, he points to Martin Luther and the struggle he had with the “theological demon of doubt,” which resulted in him throwing an inkwell at the devil. I use the example of Luther to note the important difference in duende and the demonic. Hirsch states that duende “bypasses the negative Judeo-Christian implications of demon” and that it “side-steps the moral terminology of foul possession.” I also use this example to point out something else common to heroes, their fallibility. Martin Luther’s heroism notwithstanding, his anti-Semitism created many problems. (The history of Martin Luther is beyond the scope of this paper, but a Google search using key words mentioned here will yield good information about it.)

This leads back to something else Dr. Feiner suggested, that the tendency to ask questions can lead to heroism. Question everything, he says. Don’t accept anything as dogma. Being heroic also involves knowing when to defer to others, he says. “Recognize that there are people who know more than we do, and who have thought about everything that we’ve thought about, and to not feel that we have to do it all ourselves.”

I have come to view Dr. Feiner as a hero, too. He listens to his clients and conducts himself in a way that inspires them to help themselves. Here is an example he gives of what he means by deferring to others.

We have people who have been through almost everything, the toughest things men and women have been through. They’ve been on the streets, they’ve been addicted, they have post traumatic stress disorder, they’re seeing a psychiatrist, they’re on medication. But they’ve made it through. We now have a training program for a certificate. People receiving this certificate become peer specialists. They have the capacity to connect with others in a way that even the best of us many not. And so they have a way of also making the point about being deserving in a way I haven’t thought of because I haven’t been there (personal communication, October 12, 2006).

I cannot help but think of heroism in connection to the military because many links exist. Many people view military life as adventurous, and plenty of opportunities to perform heroic deeds arise during the course of military service. James Hillman suggests we have a terrible love of war, and wrote a book with that as the title (Hillman, 2004). If it is true, as Philo has stated, that the people we meet are fighting major battles inside, the potential for a violent response from those people must exist, too. At least this would seem to be the case. We are all different, though. Nobody really knows what is happening inside another person. As was described earlier in the example showing the difference in observation and evaluation, events are witnessed differently by different people.

The internal world of a person is really only known to that person. For example, nobody but me knows what I am experiencing at this very moment. I might be in turmoil or at peace; the waters might be churning out an impending storm, or they might be so still that a perfect image can be seen in them. My friends and family might wish me well and hope that I am in a peaceful state of mind at this moment, but what if I am not? Only I really know that for sure.

James Hillman says peace is “darkness falling.” Is he correct? I read the following passage from A Terrible Love of War to Dr. Feiner.

I will not march for peace, nor will I pray for it, because it falsifies all it touches. It is a cover-up, a curse. Peace is simply a bad word…. The dictionary’s definition, an exemplary of denial, fails the word, peace. Written by scholars in tranquility, the definition fixates and perpetuates the denial. If peace is merely an absence of, a freedom from, it is both an emptiness and a repression. A psychologist must ask how is the emptiness filled, since nature abhors a vacuum; and how does the repressed return, since it must (Hillman, 2004, p. 30)?

I believe Hillman’s theory of peace shows the conflict and tension in his own mind. Does he want to do away with the “bad word” altogether, or just redefine it? In my view, it is as bad (or as good) a word as war, its opposite. War means someone will win, and that winner will force the loser to give up something; the winner will take spoils of war. In a spoils system, the ones who have become the conquerors reward their supporters in various ways. In other words, the conquered ones — the opposition that lost — become subservient to the ones who defeated them. And is this not the nature of the political beast that lives among us, too?

But now I would like to turn to what is beautiful, that which can be seen in art, as in the monuments erected to honor heroes.

When peace follows war, the villages and towns erect memorials with tributes to the honor of the fallen, sculptures of victory, angels of compassion, and local names cut in granite. We pass by these strange structures like obstacles to traffic (Hillman, 2004, p. 30).

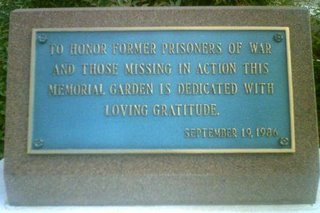

One of these memorials is shown above. It stands behind a traffic circle, in a garden inside the VA Medical Center complex. These prisoners of war are people who were being held against their will by other people who were in a position to do that. Again, in a spoils system, the winner takes what he wants, including human life.

People who have put their lives on the line, a metaphorical tightrope, for a national cause become heroes. They are honored with memorial statues and plaques such as this one.

I honor these heroes, too, yet a hero is often an ordinary person who brings something to light in an extraordinary way. Dr. Feiner is a hero because he helps disenfranchised people find dignity and meaning in lives that have gone horribly awry. I propose that a hero is a person who has faced tension and conflict with dignity and self-composure, who has moved from fear to courage in facing his battle head on.

People influence each other. How does this relate to heroism, reality, and dignity? And consider observation. Is it possible to observe without making an evaluation? Even if we automatically come to determinations (make judgments) about things, it is important to separate observation from evaluation in our minds.

Think about a person on a tightrope, a circus act. In order to get from one end of the rope to the other, the performer must concentrate on what he is doing. When he focuses his attention on the end of the rope and does not permit himself to be distracted by the distance between the rope and the ground, or of the consequences of falling from the rope, or anything else except the rope itself and staying on it, then he does just that. He stays on it. An observer might be totally unaware of what is happening inside the man on the rope. In fact, an observer might be on the edge of his seat, feeling a sense of terror over what he is seeing: a man walking across a rope that is suspended high in the air.

He is a hero! But only if he makes it. If he does not, then his act has failed and he faces not only humiliation but much more, the worst being injury or death. But regardless of whether he succeeds or fails, what the performer observes is different from a spectator’s observations. And only each one knows what that is.

So, what separates observation from evaluation, and why is it important to distinguish between the two? Here, as well as in other instances, it is a matter of tension and the potential for resistance. For the tightrope walker, I think it might be a precarious balancing act between two competing ideas in his mind, expectation of success and fear of failure. In general, however, we are talking about effectiveness.

In that space between observation and evaluation, a dance is in progress. It is a dance between This and That, between one thought and another. These dance partners are engaged in something unseen to the eye but experienced within the person who is faced with the decision of how to respond. Think of it as a flamenco dance, one in which fiery passion transforms to energy, balancing body and spirit. The dance floor can be seen as workspace here, “a place where ardor animates and sometimes trumps technique (Hirsch, page 52).” The conduct of the dancers informs our senses, wakes us up to what is alive and needing to be expressed.

Yet passion is also present in anger. Marshall B. Rosenberg, founder and director of the Center for Nonviolent Communication, addresses the topic of anger, which I also believe is important to heroism. The way a person handles anger can determine whether his actions will be heroic or not. Rosenberg says “it is not the behavior of the other person, but our own need that causes our feeling.” It is also important to note how “anger is simply absent in each moment that we are fully present with the other person’s feelings and needs.” He also asserts “it’s not what the other person does, but the images and interpretations in … [a person’s] own head that produce the anger.” (Rosenberg, 2005, pp. 143-145)

Images can lead to labeling, though. And labeling — even in a neutral sense — can distort reality, thus limiting our perception of the things and concepts being labeled. “While the effects of negative labels may be obvious, even a positive or apparently neutral label … limits our perception of the totality of another person’s being (Rosenberg, 2005, p. 28).” In the tightrope example, the observer and the performer each experience something different. The observer might be sitting in the audience and thinking about some real-life “tightrope” he is currently walking; he might relate what the man up in the air is doing to a current problem in his life, hoping and praying the guy makes it across without falling. Not only would that be a victory for the tightrope walker, but might give this person hope that his own walk across the metaphorical rope will be successful as well. Likewise, the man walking across the rope might recognize his role in the lives of the observers. If he comes through as a hero and succeeds, then everyone wins!

There is often much more going on that meets the eye. Going back to Hillman’s discussion of peace, he writes: “Books of war give voice to the tongue of the dead anesthetized by that major syndrome of the public psyche: ‘peace’ (Hillman, 2004, p. 31).” Not only did he label it things the dictionary failed to mention, he gives it yet another label: syndrome.

Does calling a thing something make it so? Not necessarily. Yet the fact that Hillman calls attention to it, and that it speaks to him in such a powerful way, says quite a bit. For one thing, it says peace means something other than what the dictionaries say it means. It also demonstrates the internal battles Dr. Feiner mentioned in the Philo quote, the ones waged within ourselves. Hillman fights the definition of peace because he knows it means something else. I have the same sense about the word, but do not necessarily share Hillman’s perception of it. What I see is as subjective as what Hillman sees.

Why do we use military terminology to describe something going on internally, within ourselves? The answer to this question could tie in to why brave acts performed in a military context are considered heroic. In the military hero, Hillman writes, “a transcendent spirit is manifested.” Returning to Marshall B. Rosenberg, he asserts that context matters in nonviolent communication (NVC), specifically with regard to separation of observation and evaluation. Rosenberg writes: “NVC is a process language that discourages static generalizations; instead, evaluations are to be based on observations specific to time and context (Rosenberg, 2005, p. 26).”

Looking at heroism in a military context, I return to Hillman. He points to one sentence from the movie Patton as being a good summary of what his book attempts to understand.

The general walks the field after a battle. Churned earth, burnt tanks, dead men. He takes up a dying officer, kisses him, surveys the havoc, and says, “I love it. God help me I do love it so. I love it more than my life” (Hillman, 2004, p. 1).A hero is someone who has the grace of a dancer and the will to look for salvation within each battle. It is not an easy task. Hillman (2004) talks about the “salvational aspect of battle.” I believe our battles are waged on a level that sometimes even we do not understand. Just as it is almost impossible to wrap our minds around the complexities of the brain, and the conscious mind and how it might connect to (and be separated by) the subconscious and unconscious mind, we also cannot fully grasp the meaning of some of the “battles” we encounter in our daily lives. Furthermore, what happens in the subconscious and unconscious mind might or might not be a “brain” function; these realms could possibly be contained within the nervous system or some other inner working system of the human body. My point here is that there are some things we might never understand.

The ways in which internal wars are waged might very well be not only obscured from our view but something that can never be known! We know they are going on inside, but we cannot quite point to why or how. We can search for meaning and come up with reasons. One of them might be simply that life is struggle. That can explain partially why we are so often at war with ourselves.

Nature informs us otherwise, though. Does a flower, for example, struggle to bloom or does it just bloom? I am looking out a window at a pink flowering tree. I cannot see any struggle taking place; all I see is a peaceful tree, swaying gently in the breeze. What is happening within that tree is “known” (experienced) only to the tree itself. We can observe it, even film it over an extended period of time. If we keep the camera running long enough, we will observe the flowering of the as yet unopened buds. But we cannot accurately call the process “struggle.” That is an arbitrary and limiting label.

Nature informs us of our limitations in many other ways, too. Confined within our bodies, we discover how needy we really are. We must eat, drink water, and eliminate our bodies’ waste products; we must, we must, we must. Just as the flower must bloom, our nature is to be who we are.

These existential realities lead back to the idea of meaning in life. Frankl (1984) discusses meaning in relation to death. Another author, Bill McKibben, links death to heroism: “Without the possibility of death, heroism would disappear — and heroism has always been one of the deeply human callings (McKibben, 2003, p. 159).”

Monuments are built to honor heroes of all kinds: political leaders, scientists, artists, soldiers, social activists, and more. Yet the hero is a human being, fallible and sometimes weak. Martin Luther King, Jr. was named after a famous theologian who accomplished many heroic feats, yet his anti-Semitism remains evident. I’m sure the doctor who saved my life at birth has his foibles and weaknesses, too. But it takes nothing away from what he did on that day of my birth. The homeless veterans who are served by the VA medical system, in particular the ones who become peer specialists, are heroes.

You and I and each person who chooses to face reality with dignity, however grim or unbearable it might seem at times, are heroes, too. If we do not view ourselves as such, we might not recognize the opportunities for heroism that enter our lives. A healthy balance of appreciation for all heroes — past and present, ourselves included — will help us appreciate also the necessary process one must go through to achieve that status and reap its rewards. Like the tightrope walker who beams triumphantly at his audience upon reaching the end of the rope, the ordinary person can achieve a similar satisfaction at his own conduct when he: first, observes and recognizes how it is chosen and second, exercises restraint and measured judgment of what he comes to observe. All it takes is focus and attention to detail, with a goal in mind.

References

Frankl, V.E. (1984). Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy (Touchstone ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Hillman, J. (2004). A Terrible Love of War. New York: The Penguin Press.

Hirsch, E. (2003). The Demon and the Angel: Searching for the Source of Artistic Inspiration (First Harvest ed.). Orlando, FL: Harcourt, Inc.

McKibben, B. (2003). Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age. New York: Owl Books, Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Pickett, Joseph P. (Ed. Et al.). (2002). The American Heritage College Dictionary (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Rosenberg, M.B. (2005). Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life (2nd ed.). Encinitas, CA: PuddleDancer Press.

Santrock, J.W. (2006). Life-Span Development (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Schneider, P. (2003). Writing Alone and with Others. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment